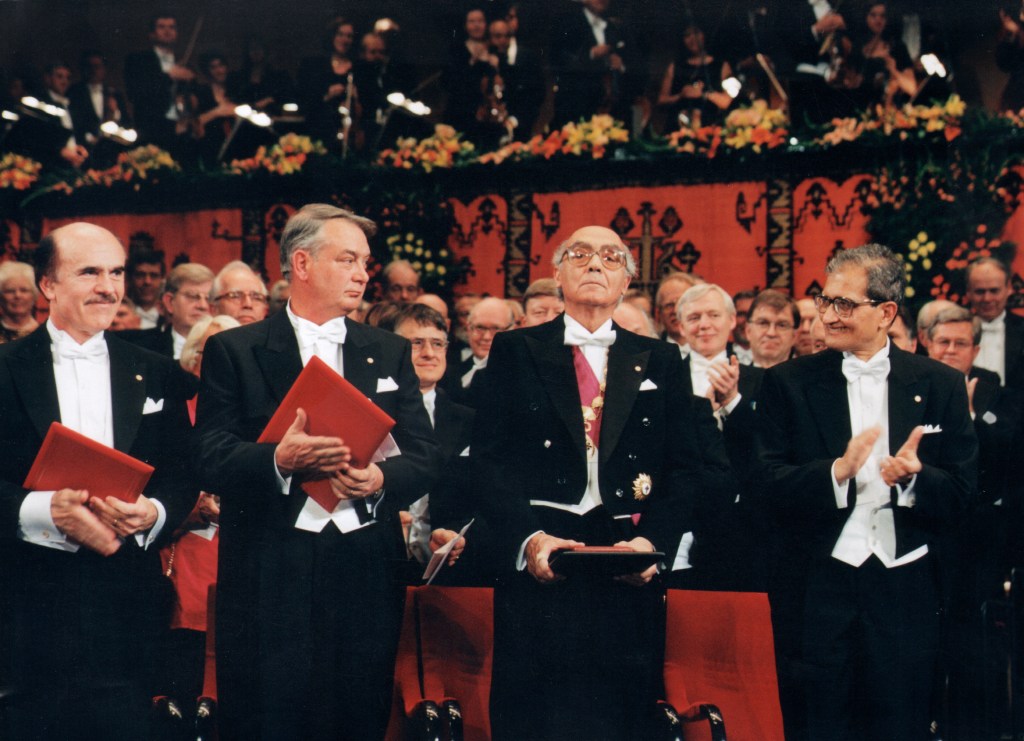

On 10 December 1998, the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, José Saramago spoke to the Nobel Academy as the winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature. His words were a reminder of the need to enforce a document that many saw as outdated, but which, if honoured, would make the world a better place. From this speech came the embryo for the creation of a Declaration of Duties, because no right is fulfilled without the symmetry of its duty.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights was signed today exactly 50 years ago. There is no lack of ceremonial commemorations. The attention fades, you know. When serious matters emerge the public interest starts to diminish, the next day even. I hold nothing against these commemorative acts. I myself have contributed to them, in my modest way, and if it is not out of place or time or ill-advised let me add some more.

As a declaration of principles, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights does not create legal obligations for states, unless their constitutions state that the fundamental rights and freedoms recognised in them will be interpreted in accordance with the Declaration. We all know, however, that this formal recognition can end up being distorted or even denied in political action, economic management and social reality. The Universal Declaration is generally considered by the economic and political powers, even when they presume to be democratic, to be a document whose importance does not go much further than the degree of good conscience it gives them.

In this half-century, obviously governments have not morally done for human rights all that they should. The injustices multiply, the inequalities get worse, the ignorance grows, the misery expands. This same schizophrenic humanity that has the capacity to send instruments to a planet to study the composition of its rocks can with indifference note the deaths of millions of people from starvation. To go to Mars seems more easy than going to the neighbour.

Nobody performs her or his duties. Governments do not, because they do not know, they are not able or they do not wish, or because they are not permitted by those who effectively govern the world: The multinational and pluricontinental companies whose power – absolutely non-democratic – reduce to next to nothing what is left of the ideal of democracy. We citizens are not fulfilling our duties either. Let us think that no human rights will exist without symmetry of the duties that correspond to them. It is not to be expected that governments in the next 50 years will do it. Let us common citizens therefore speak up. With the same vehemence as when we demanded our rights, let us demand responsibility over our duties. Perhaps the world could turn a little better.